Last year, the Canadian Broadcasting Corporation (CBC) reported criticism against journalist Joe Sacco’s graphic novels. “It’s not a cartoon. It’s not a joke, […] it’s something really f–king serious,” said one man in reference to Sacco’s latest graphic novel, Paying The Land (2020), on the forgotten history of the Dene people indigenous to Canada’s Northwest Territories. This scathing comment reignited the debate on how to appropriately represent human rights violations in the media.

Sacco’s journey to uncover forgotten Palestinian history can shed light on this debate. One of Sacco’s most famous novels, Footnotes in Gaza (2009), showcases the important contributions his novels make to our understanding of human rights abuses in Palestinian history. It recounts his quest to uncover the forgotten stories of two massacres, those of Khan Younis and Rafah, committed surreptitiously by the Israeli army during their invasion of Suez in 1956.

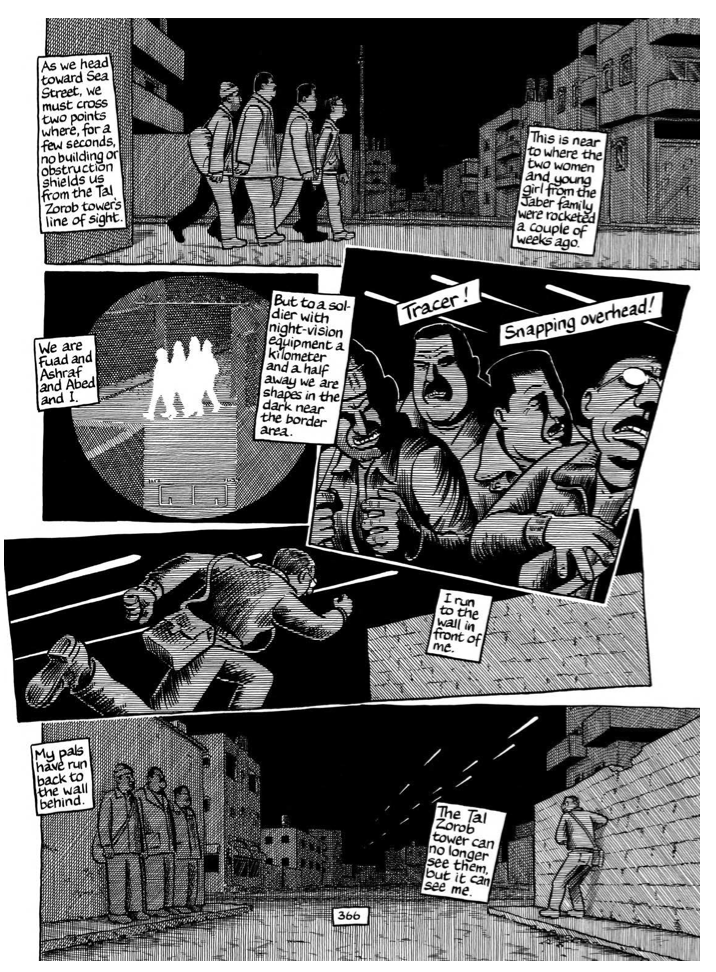

Sacco, depicting himself—somewhat self-deprecatingly—as a round-headed, childish, big-nosed outsider, lives among his subjects, braving the gruelling and perilous conditions of the Israeli occupation to tell his story. For instance, he reports narrowly avoiding death when Israeli snipers fire at him and his friends in the dark. It is a visceral reminder, for Sacco, of the indiscriminate nature of Israeli violence.

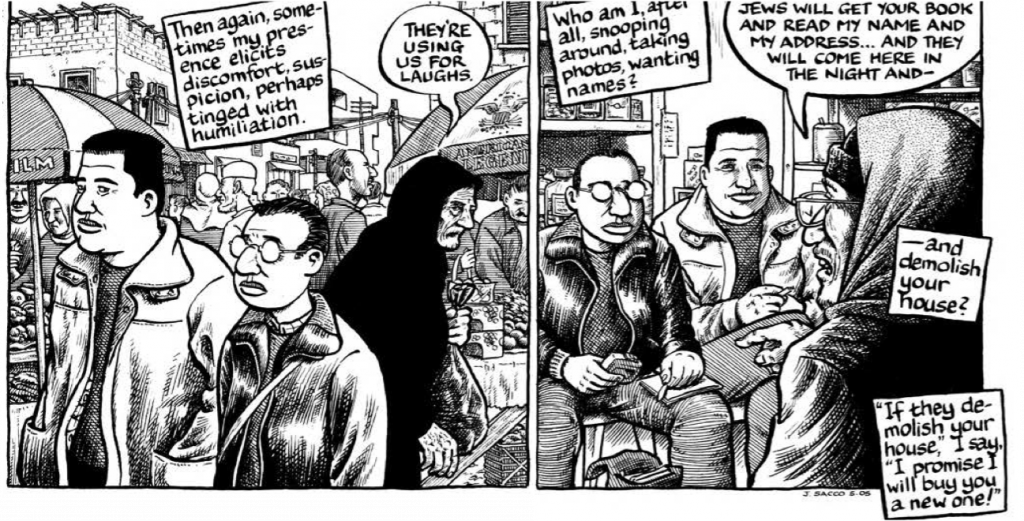

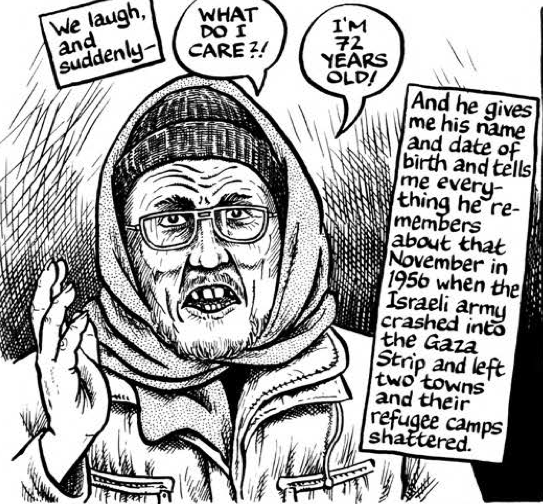

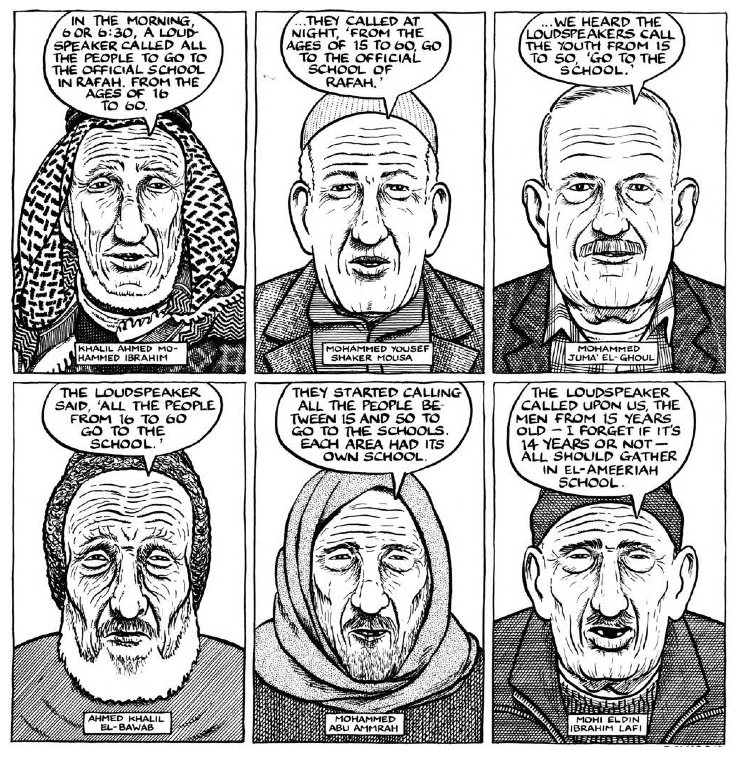

Sacco aims to recover lost historical facts by interviewing elderly residents who witnessed these massacres. Sacco mainly interviewed people who volunteer their information, although this came with a risk. The ever-present threats of violence and destruction deterred younger people from helping Sacco in his search for evidence because they were, after all, responsible for families and various occupations and risked losing it all by exposing their identities in order to testify.

Sacco thus mainly interviewed older Palestinians who believed they had less at stake by sticking their necks out to tell their stories.

Seeing young Palestinians forego the chance to understand their past and, ultimately, the potential to receive justice in order to save their livelihoods and the little control they had over their lives was, for Sacco, evidence of the desperate living conditions in Gaza.

Sacco also illustrates the deplorable living conditions that push them to such desperation. His artwork exposes readers to the ways that the atrocities of 1956 continue to traumatize victims and affect the patterns of daily life even in 2003 when Sacco was conducting his research.

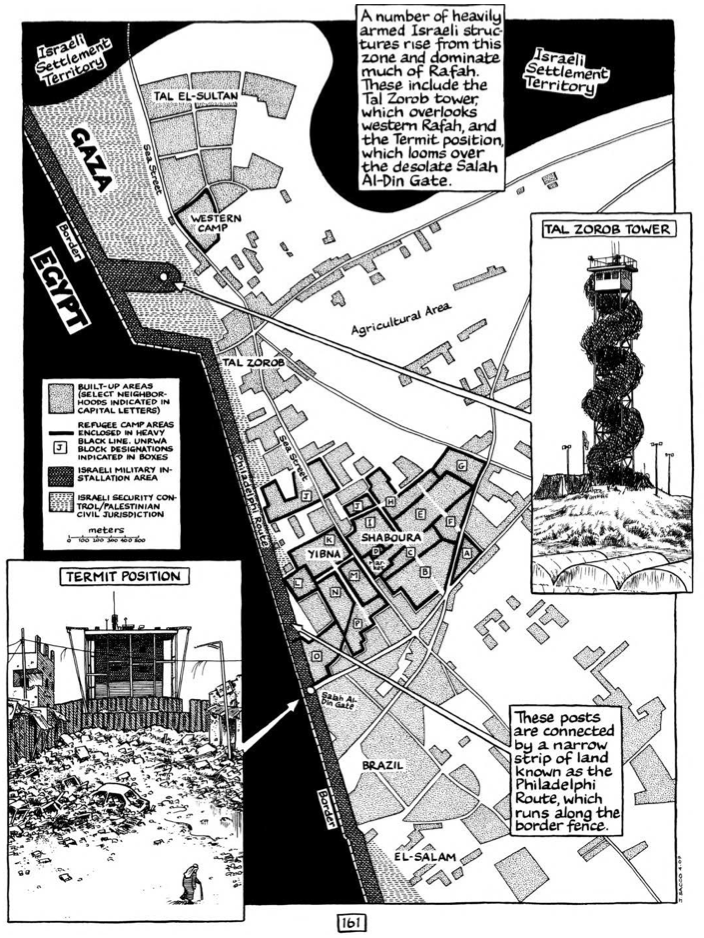

For instance, he draws a map of Rafah and superimposes photo-style drawings of the landmarks on the map. In an image showing the Israeli “Termit” stronghold, Sacco captures the rubble it is built upon alongside an old man as he moves past the destruction.

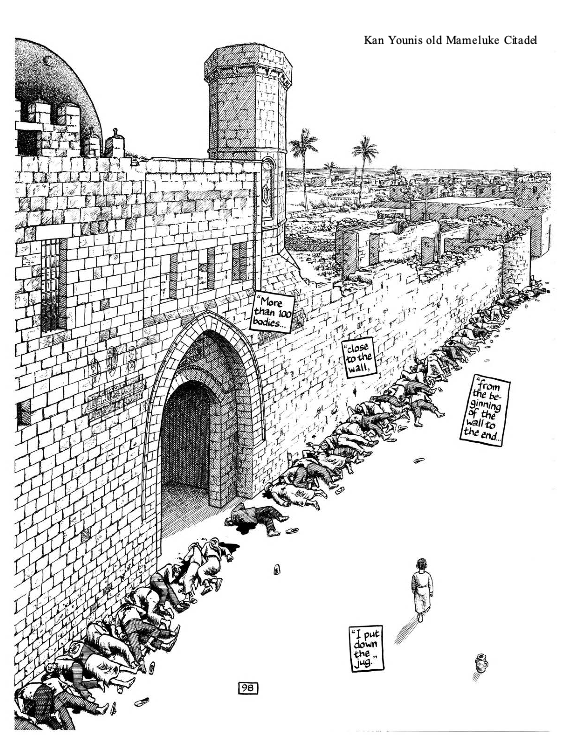

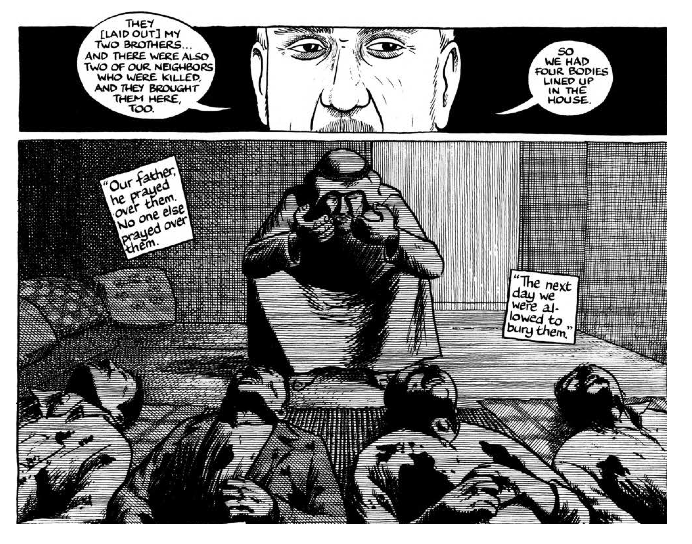

Sacco takes similar care to reproduce the small yet tragic details of his witnesses’ stories alongside the facts relevant to the 1956 massacres. Takreem al-Batta from Khan Younis told Sacco how his father spent many sleepless nights alone praying for his two elder brothers and two other neighbours – who had no one alive to pray for them – after they were called out and shot by Israeli soldiers. These personal details are weaved with the journalistic-style reporting on the facts, such as the locations of mass killings on Khan Younis’ old Mameluke citadel’s walls and central streets. He draws everything from wailing mothers and private prayers to mass violence inflicted on Palestinian communities.

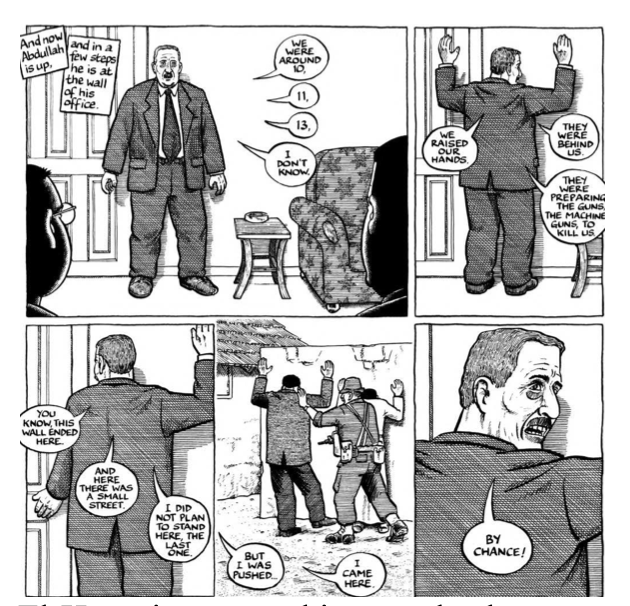

Sacco’s artistic method exposes the weighty reality of the past since he draws his present-day story in the same artistic style as he draws the atrocities of the past. The past and present look the same in his novels. The witnesses express the same terror in experiencing atrocities in 1956 as they do while retelling their stories five decades later.

In one case, Dr. Abdullah El-Horani recounts his near-death experience. Pinned against a wall by an Israeli Army firing squad, his last chance to escape was by gambling that no one was pointing their gun at him and bolting to the nearest alleyway.

Despite using cartoon illustrations, Sacco does not compromise the thoroughness of his journalism.

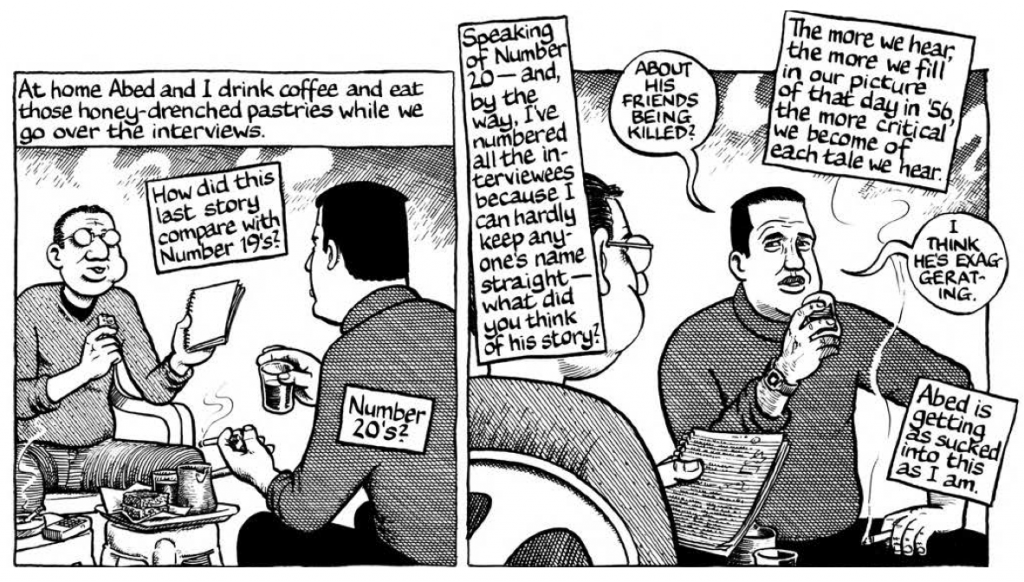

To reconstruct a given event, he interviewed several witnesses and cross-examines their different narratives to establish similarities.

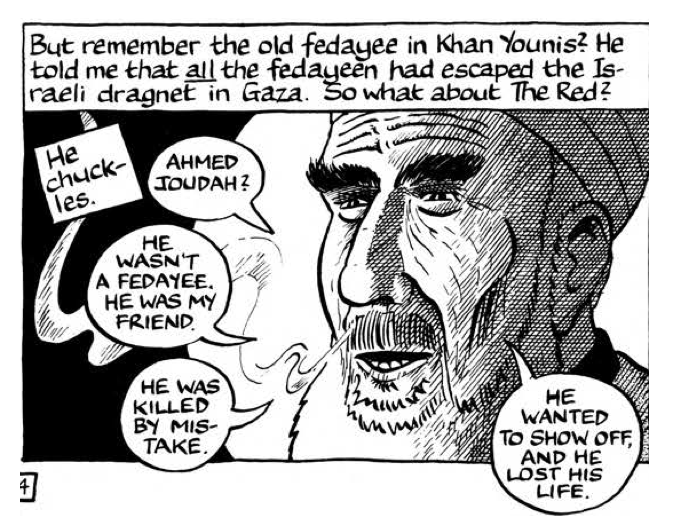

Sacco found a hole in the story of one fidayee he interviewed.

This fidayee mentioned that there were no militants captured during a specific Israeli operation, yet Sacco learned that one militant, nicknamed “The Red” was, in fact, missing.

In finding many similar missing details, Sacco and his team of journalists admit being skeptical of exaggerated details. Sacco’s readers are thus privy to his methodology, and he constructs many historical testimonies this way.

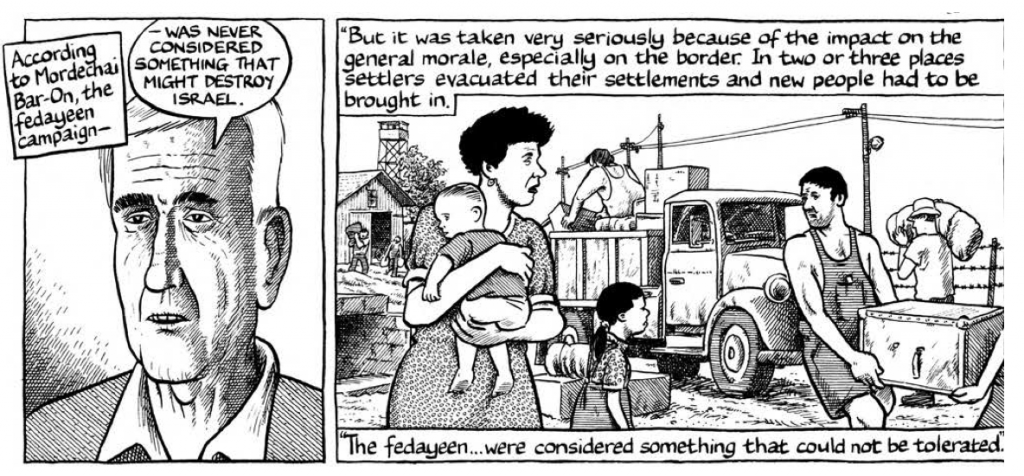

His thoroughness leads him to locate sources from both sides of the conflict. He interviewed Mordechai Bar-On, the Chief Education Officer and Head of the Department of History of the Israeli Defense Forces in 1956, who testifies to how high-ranking Israeli officials were constantly calculating population demographics and how fidayee intimidation campaigns would impede their plans to relocate Jews into Arab-majority areas.

Sacco’s journalism stands out from the work of his contemporaries since he exposes aspects of Palestinian history only available to specialized academics and Palestinians themselves. One of these topics explored is the expression of national honour through Palestinian womanhood.

For instance, scholars, such as Frances Hasso, examined how the generation of Palestinians growing up before the Arab defeat in 1967 equated Palestinian women to their national honour. However, Sacco adds an important personalized dimension to this understanding, as he illustrates his struggle to understand this way of thinking and deconstruct his Westernized preconceptions of individual identity and national honour. Sacco thus illustrates this complex relationship between gender and nationalism in a novel way that both informs members of the public and provides a personal reflection on the intricacies of understanding such concepts.

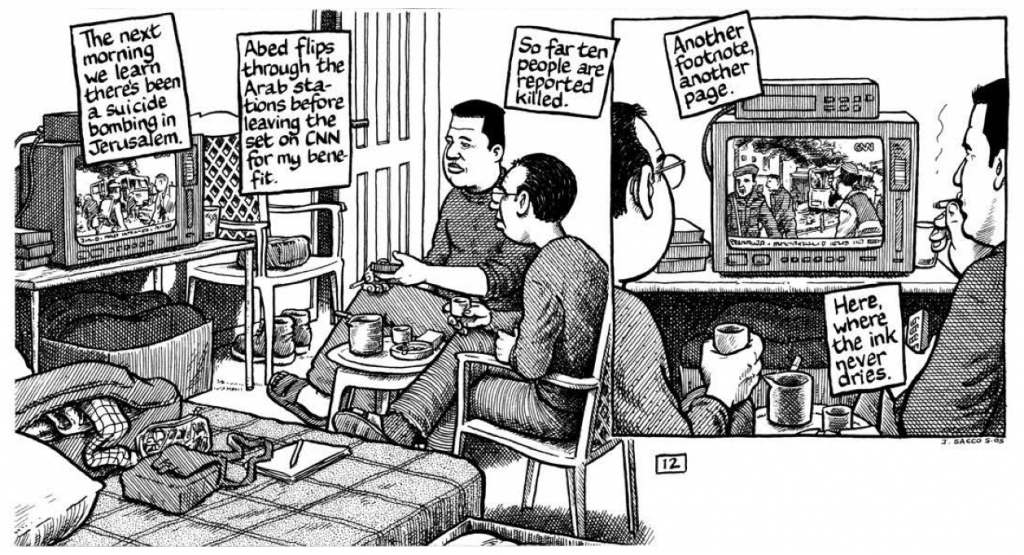

Sacco’s work is also valuable for exposing an important critique of traditional media. The saturation of the infosphere with so constant news of violence makes new transgressions reported appear “normal.” Gradually, the public thus becomes desensitized to the continued strife against Palestinians. Moreover, he explicitly critiques CNN for its complicity in overlooking the violence in Palestine in favour of more “breaking news” since CNN considers the human rights abuses in Palestine to be repetitive, and therefore unappealing, stories. It thus opens avenues for future investigation into the traditional media’s role in silencing atrocities in Palestine.

Ultimately, it is precisely through Sacco’s unorthodox style of writing and commitment to integrous journalism that readers can understand such human rights abuses in a new light. Indeed, he opens many points to further exploration, including his critique of traditional media and his critique of his own Westernized preconceptions. Overall, whether abuses occur in the Occupied Palestinian Territories, Canada’s Northwest Territory, or wherever history’s footnotes are relegated, Sacco’s trademark journalistic style disillusions and fortifies our understandings of violence in the world’s most overlooked regions.

Bibliography

“Joe Sacco.” New York Review of Books. Last Modified May 19, 2012. https://www.nybooks.com/contributors/joe-sacco/.

“Paying the Land.” Macmillan Publishers. Last Accessed on December 9, 2021. https://us.macmillan.com/books/9781627799034/payingtheland.

Cockburn, Patrick. “‘They Planted Hatred in Our Hearts.’” New York Times Review of Books. Last Modified on December 24, 2009. https://www.nytimes.com/2009/12/27/books/review/Cockburn-t.html.

Hasso, Frances S. “Modernity and Gender in Arab Accounts of the 1948 and 1967 Defeats.” International Journal of Middle East Studies 32, no. 4 (2000): 491–510. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0020743800021188.

Sacco, Joe. Footnotes in Gaza. London: Jonathan Cape, 2009.

Toth, Katie. “Renowned cartoonist says his new book on Dene history helped decolonize part of himself.” Canadian Broadcasting Corporation. Last Modified on July 7, 2020. https://www.cbc.ca/news/canada/north/joe-sacco-nwt-dene-comic-graphic-novel-1.5640360.

Timothy is a fourth-year undergraduate student of History and Political Science. His research focuses on the history, evolution, and contemporary expression of identity in the former Ottoman territories, particularly the Eastern Mediterranean. He has completed numerous projects focusing on, among others, the impact of German orientalism on the cartography of Palestine, as well as several aspects of the political, cultural, and social history of Palestine during the late Ottoman and British Mandate periods. He hopes to pursue this interest at the Master’s level.