While Palestinian resistance against Israeli oppression and apartheid takes on many forms, Palestinian fashion, in particular, has become a space for designers to use traditional Palestinian embroidery and textiles to resist the erasure of Palestinian history and culture. This is because one of the consequences of settler-colonial projects like Zionism is taking pre-existing cultures and erasing them, or co-opting them as their own (Khalidi 362). Palestinian fashion has not escaped this reality either. The brands mentioned often have to resist violent occupational forces to operate and survive. This take on resistance is particularly powerful because many of these brands are led by and support Palestinian women. Within the Palestinian Nationalist movement, the often patriarchal traditions around protecting Palestinian women made it more difficult for them to participate or have an active role in the resistance efforts (Hasso 492). Specifically, members of the nationalist movement during the 1948 and 1967 wars mostly accepted masculine norms which required men to protect women’s bodies and their autonomy from other men, thus keeping women away from politics overall (Hasso 492).

Of course, in the post-1967 period, there have been many women who have risen against the “old ways” and endured a struggle whereby they can participate more actively in both waged work and nationalist activity (Hasso 503). During the first Intifada, women played a central role even in leadership positions because many men were imprisoned (Khalidi 255). One of the ways that women have supported the fight for Palestinian freedom is through the creation of revolutionary clothing. In this process, Palestinian brands have overcome barriers created by the Israeli Apartheid and employed women from Gaza and the West Bank. These women have continued to use traditional techniques to combat the erasure of their culture. These efforts have also helped spread Palestinian culture around the world. In fact, many Palestinian poets like Mahmud Darwish have written about how cultural resistance has the ability to counteract colonial attempts to erase Palestinian identity (Nassar 93). In the following pages, you will learn more about cultural resistance as it is practised by Palestinian brands.

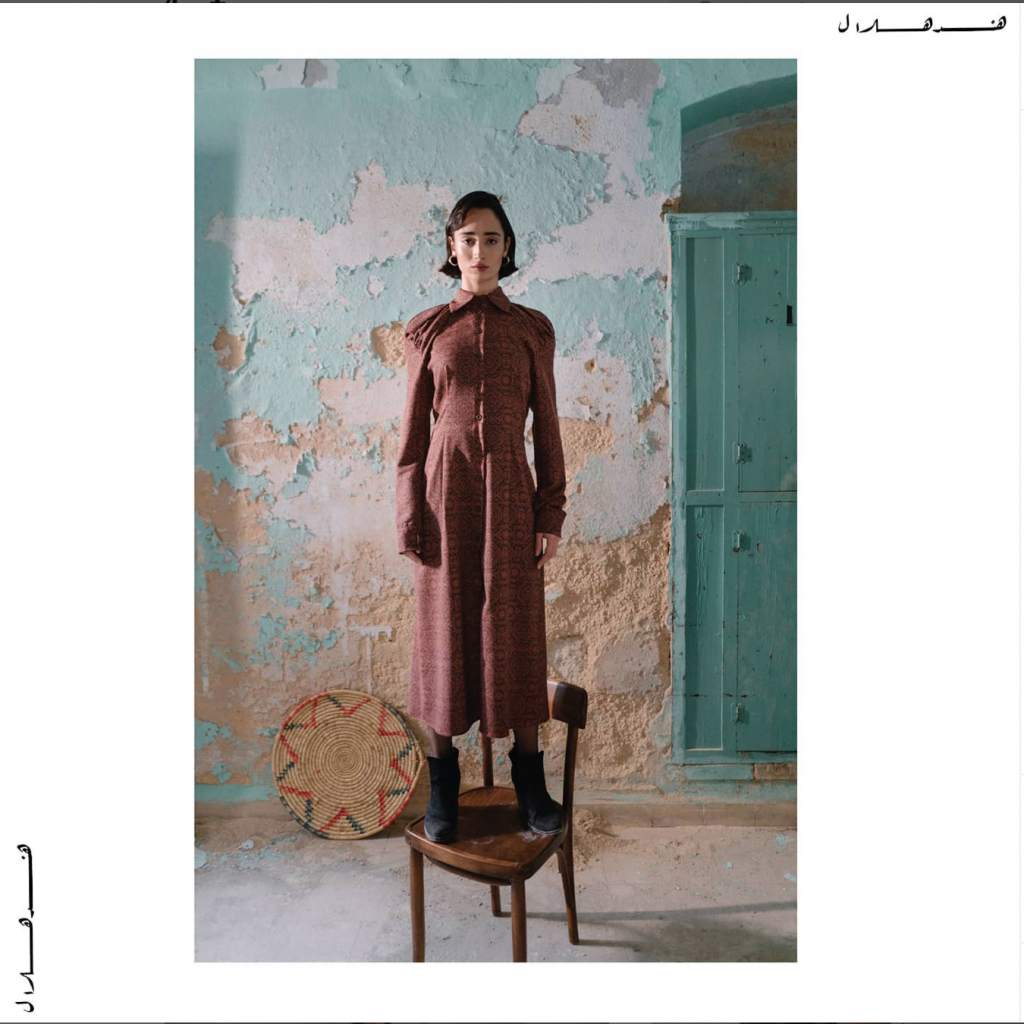

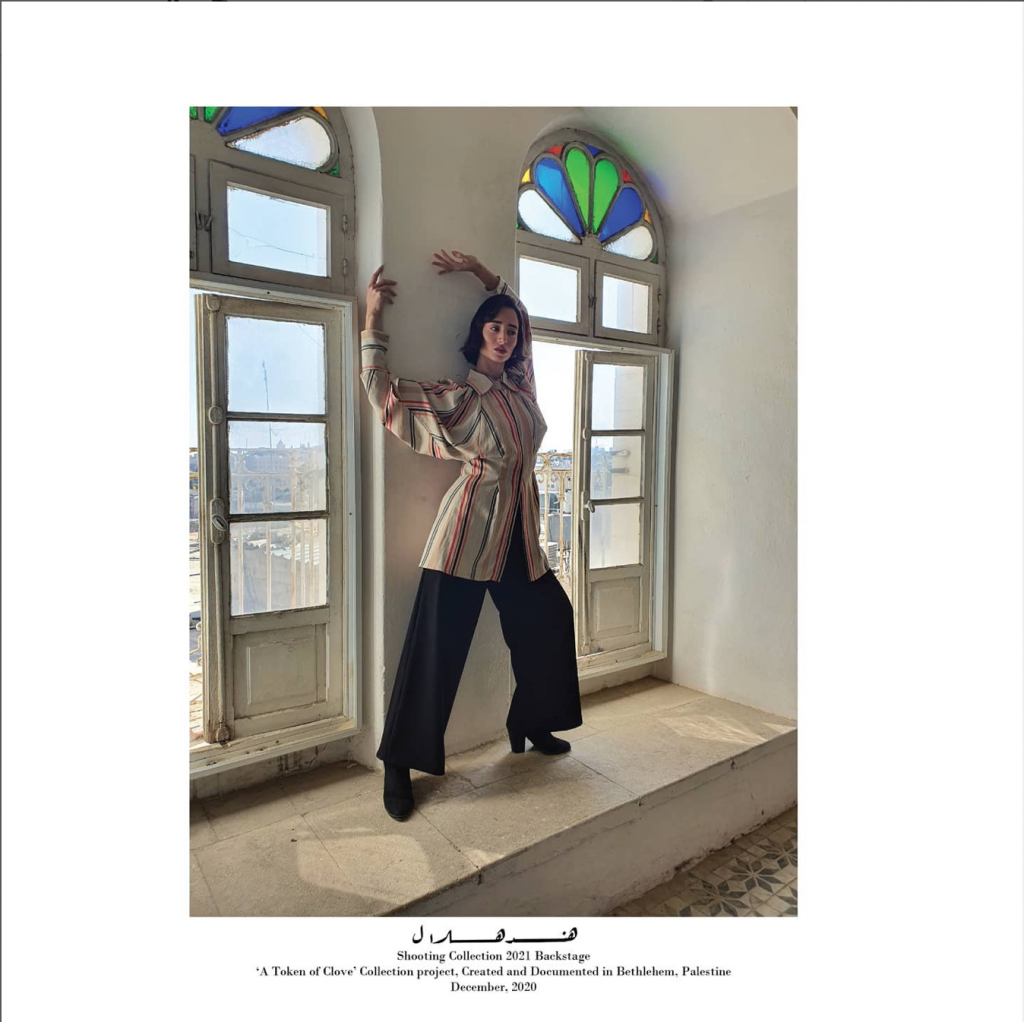

HIND HILAL

Hind Hilal is a Palestinian ready-to-wear brand founded by a Palestinian designer and architect, Hind Hilal, who originates from Bethlehem city (Hind Hilal). Hind grew up under occupation in Palestine. She fought to create her brand and continues to face struggles due to delays from checkpoints, lack of resources and, the need to compete with Israeli brands for workers (Hind Hilal). Her journey shows perseverance in the face of the Israeli Occupation, which was responsible for taking away and “stealing” the land which her ancestors cultivated for generations. This is depicted in the poem, Identity Card, in which Mohammad Darwish says, “I am an Arab, Robbed of my ancestors’ vineyards and the land cultivated by me and all my children. Nothing is left for us and my grandchildren.” The Occupation has resulted in low resource availability for Palestinians. But despite these hardships, Hind has said that using the little she has to create authentic and loud pieces which reach further has become her form of resistance and existence as a Palestinian and a designer (Kahil 2021).

DAR NOORA

Dar Noora is a brand by Palestinian designer Noora Khalifah based on her personal experience in Jerusalem. It combines both modern fashion and traditional Palestinian cross-stitch, or hand-embroidery, also known as tatreez. (Dar Noora). The brand is also on a mission to empower and give a new voice to women who have carried the tradition of tatreez through Palestine’s history (Dar Noora). The brand employs and provides women across Gaza, the West Bank, and Jerusalem with the opportunity for empowerment through their tatreez and stitchwork (Dar Noora).

MEERA ADNAN

Meera Adnan is a contemporary Palestinian brand which operates from Gaza city. The brand focuses on reclaiming the Palestinian narrative and drawing from religious, political and local references to create “a romantic and nostalgic visual monologue from a city under siege,” (Meera Adnan). Meera Adnan’s goal is to develop a platform for Palestinian creativity and revive the local textile for future Palestine (Meera Adnan). It represents cultural resistance, particularly through its fight to survive under the tough conditions Palestinians are subjected to in Gaza.

TEITA LAILA

Taita Leila is a Palestinian social enterprise that produces high-quality, modern clothing inspired by the long and rich traditions of Palestinian embroidery. The pieces are hand-embroidered in Palestine by women in the West Bank (Taita Leila). Taita Leila is bought and appreciated by customers worldwide, demonstrating the solidarity and support people have for Palestine, and Palestinian-owned businesses as well.

NÖL COLLECTIVE

Nöl Collective is an intersectional feminist and political fashion collective based out of Palestine (Nöl Collective). The brand’s objective is to unite people over shared struggles (Nöl Collective). Nöl also focuses on highlighting the human nature of fashion and politics. More than just a fashion label brand, Nöl works at the intersection of Palestinian culture, feminism, ethical fashion, and social justice (Nöl Collective). From start to finish, its garments are sourced, sewn and embroidered all across Palestinian cities by small family-run businesses and women’s cooperatives. Nöl’s production process helps with the revival of the local textile industry and particularly women artisans and develops a network of creatives across Palestine (Nöl Collective). Nöl believes that its garments represent how the creative process and the collective can transcend physically imposed borders, making each item an act of defiance (Nöl Collective).

DARZAH

Darzah is a non-profit ethical fashion brand dedicated to empowering women in the West Bank by curating and providing a platform to showcase their work (Darzah). People who shop from the brand are able to directly financially support 26 female artisans in Palestine, as 100% of the products are made in the West Bank, specifically in Al-Khalil/Hebron (Darzah). Darzah focuses on creating authentic, handmade Palestinian products, especially by using the traditional, generationally taught Palestinian Tatreez, which has been passed down through generations of women over several centuries (Darzah).

ANAT

Anat International is an avant-garde streetwear brand from Gaza, Palestine (About Anat). Anat defines its brand as a “global force which transcends boundaries and breaks norms” (About Anat). The brand uses traditional Palestinian embroidery to honour its beauty and history. It also produces clothing that is meant to be worn by all genders. Not only is the brand resisting occupation by celebrating and maintaining Palestinian art, but it is also adopting a slow-fashion approach to protect human labour and our environment (About Anat). Anat does not manufacture its products in bulk in order to focus on employing local artisans in Palestine that take time to produce each piece ethically and sustainably.

HONOURABLE MENTIONS

- Deerah

- Dar Collective

- nnbynn

- Hirbawi Keffiyeh Weavery

- Watan

- Inaash Association

- Sulafa Embroidery Center

Nivaal Rehman is a third-year student pursuing a double major in International Relations and Peace, Conflict and Justice Studies. Her research interests include settler colonialism, occupation, Islamophobia and the history of oppression, particularly in the cases of Palestine and Kashmir. Outside of university, she is an activist, filmmaker, journalist and the Co-Executive Director of her non-profit, The World With MNR. She is dedicated to addressing gender equality, climate justice, inclusivity and human rights issues, especially through storytelling, on her organization’s social media platforms.

https://palestinestudies.artsci.utoronto.ca/resistance-through-the-thread/